The risk of kidney disease has been growing in poor neighborhoods, according to research at Loyola University Chicago.

More than a third of new U.S. dialysis patients between 2005 and 2010 lived in ZIP codes where 20 percent or more residents live below the poverty level, compared to 27 percent from 1995 to 2004. Based on patients in the United States Renal Data System, the study is believed to be the first tracking poverty and dialysis cases over time.

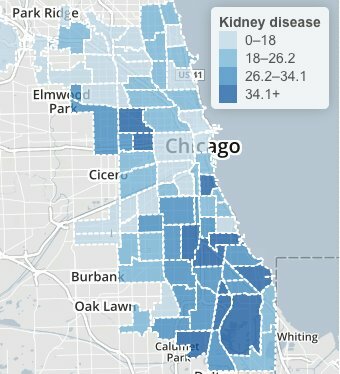

The high rates mirror Chicago Department of Public Health figures for 2006 to 2010. As charted in the Chicago Health Atlas, 10 of the 11 community areas with the highest death rate from kidney disease had one-quarter or more households that fit the federal definition of poverty. Poor neighborhoods also see conditions that are risk factors for kidney failure, from diabetes and obesity to high blood pressure and heart failure.

In this edited transcript, Smart Chicago discusses the findings with corresponding author Dr. Holly Kramer, an associate professor in nephrology and public health sciences at Loyola’s Stritch School of Medicine.

In 1.25 million cases, the rate of kidney disease grew overall, and grew more in low-income ZIP codes. What’s at work with these changes?

We linked information from the United States Renal Data System with the U.S Census. We grouped people who initiated dialysis from 1995 to 2004 with the 2000 Census, and then used the ZIP codes that they report. We used the census data to determine how many of those people in those ZIP codes lived below the federal poverty line.

And then we just looked at the association between poverty status and dialysis initiation, using all the ZIP codes where people had end-stage renal disease. The association between poverty and end-stage renal disease incidents was a little big stronger during the latter period, by about 3 percent.

That could certainly be just a random finding, but I think it’s plausible because our measurement of poverty status, the federal poverty line, hasn’t really changed over the past 50 years. Yet the need for making it in society, making sure you have access to nutritional foods, having access to health care, being able to afford your medications, that has dramatically changed.

So you didn’t have information on income of each patient. Would that have been a better predictor of kidney disease risk?

Probably. There are studies that show that individual measures of poverty, if someone just self-reports their income, is going to be a more sensitive indicator of poverty status.

But certainly areas of poverty have no grocery stores, no access to fresh fruits and vegetables. I work in Maywood, and maybe there’s one grocery store in one remote part – there’s no subway system, it’s very difficult for people to exercise, there are no gyms. So if you live in a poverty area it’s going to affect your health.

Those proportions, from 27 percent to 34 percent, either way those are striking rates. Why are so many dialysis patients poor?

If you’re poor your diet is going to be different. Your day to day lifestyle will be different, your access to health care may be different. If you do develop diseases you may not have the disease detected until much later because you’re much less likely to get routine treatment of blood pressure and diabetes. Sometimes it might be too late. You might have substantial organ damage from undetected diabetes.

The same thing is with hypertension: If you’re eating a lot of processed foods, sodium is going to accelerate blood pressure. High blood pressure is a really high risk factor for kidney disease. It’s really problematic. I see kids walking down the street with a 16-ounce Coke and a bag of Doritos at 8 in the morning, and their blood pressure is going to be higher than kids who eat healthy breakfasts. For all their other meals as well, more processed foods means a lifetime of exposure.

Would you have predicted improvements over time, because health care has advanced?

If you look at overall dialysis incidence, you are seeing plateaus and even a small decrease. That reflects better, aggressive blood pressure and diabetes control, and maybe even some screening.

But any kind of chronic disease takes decades to develop. We’re probably not going to see much change for several years. Hopefully the Affordable Care Act makes health care more accessible., and more emphasis on public health will have impact as well.

You mentioned toxins in the study as well.

It’s well known that lead toxicity can affect your kidneys, and chronic lead toxicity is associated with gout, hypertension and chronic kidney disease. That’s the triad. Chicago once had one of the highest levels of acute lead poisoning among children. A lot of people have been trying really hard to eliminate lead exposure. Loyola University Chicago was one of the big proponents.

What are the challenges in low-income areas in managing kidney disease? Are there clinical responses to underserved areas this study would indicate?

It’d be really great to make access to healthy foods more accessible to people who live in poor neighborhoods. That should be a basic right. If people live in a neighborhood that doesn’t have grocery stores they can walk to, they get their food from the gas station and eat carryout. This is really driving chronic disease incidence and making it really difficult to manage chronic diseases. How are they supposed to be eating less salt if everything they’re eating is processed?

The second thing would be more local access to clinicians, more neighborhood clinics. A lot of people are travelling really far, waiting a long period of time, paying parking fees and car payments. It shouldn’t be so arduous.

Chicago Health Atlas: Kidney disease deaths, 2006-2010

This is a study of U.S. patients. Can the findings be extended to Chicago? What are the lessons for Chicago health workers?

Chicago does have very high rates of death from kidney disease. If there were more health infrastructure, definitely we could be an excellent model for reducing chronic diseases.

The National Kidney Foundation of Illinois has a van that they drive around to different areas. Nurses and physicians and other health care workers volunteer. They screen for blood pressure and diabetes, and they give counseling and help people find physicians if they’re having insurance issues. That’s a great example of an advocacy group trying to do something to help people with chronic diseases. The American Kidney Fund has also done pre-screenings for kidney disease, diabetes and hypertension.

Hispanic patients grew from 11.5 percent of the cases in the early period to 13.9 percent later.

Hispanic adults have about 100 percent higher risk for end-stage renal disease. Some of that could be access to care. The Affordable Care Act does give access to insurance for people who are legal in the United States, but not to the undocumented.

You say in the study that “poverty itself is not static” – it has increased over time. Is the rate the same in the patient and general populations?

The change in poverty status in the total U.S. population is not that big; the change in the dialysis population exceeds that.

The time is framed in two periods, 1995 through 2004 and 2005 through 2010. Why were these periods chosen?

We wanted to make sure each group was within five years of the census. The later period includes years before the recession, but some of the drive in rates during the second part could be because the recession in 2008 changed a lot of people’s poverty status.

Would a year-over-year study show the same trend?

We’re hoping someone will take an interest in what we do, and use more refined measurements of poverty status. But we have to stop thinking of poverty as yes-or-no. It’s a very dynamic thing. Ten years ago you didn’t have to have a computer or cellphone to be an integral part of society.

You tracked patient age as well. The patient population was getting a little older.

The highest incidence of dialysis treatment is among people over age 75 now. As you age you lose kidney function, lung function, memory fades. Sometimes kidney disease is due to the success of people not dying from stroke and heart attack. We’re better at controlling their lipids and their diabetes, so they live longer.

It’s a confluence of factors – hypertension, obesity, high cholesterol – that leads to so much serious illness.

Poverty seems to impact end-state renal disease more than any other chronic disease. It’s such a shame because Medicare pays for all dialysis. It’s extremely expensive. If we did more to prevent kidney disease we could spend a lot less. Big dialysis companies are making a lot of money off of our poor public health infrastructure to prevent kidney disease.