This post is about designing a taxonomy for Chicagoland’s data ecosystem, and why a taxonomy would be useful for the growth and development of the ecosystem.

Taxonomies are used in many disciplines to organize knowledge. Carl Linneaus’s taxonomy to classify species — like Homo sapiens — is used today, almost three hundred years later. It’s a good example of a nested hierarchy, where each category is a subset of a broader category. A strong taxonomy has a notation convention for classifying individual items and an organizing principle (or principles!) for putting items in relationships with each other. Structured lists, alphabetical order, numerical order, headers, indexes, tables of contents, the branching diagram, all kinds of finding aides — these things are so common now, most people take reference tools for granted. So what?

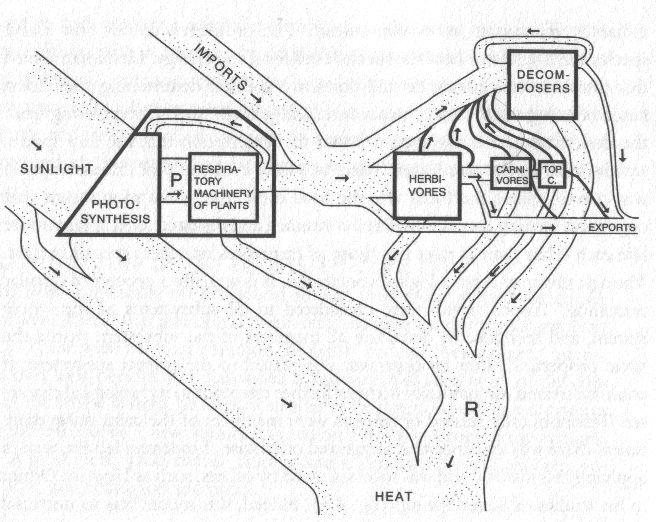

This is a diagram from Howard T. Odum’s 1971 study of Silver Springs, Florida, an early, pioneering effort to model the thermodynamic and material flows for an ecosystem. What are the elements of a data ecosystem?

The Ecosystem Project

The warrant for Smart Chicago’s “ecosystem project” is to build with, not for, to be at the service of people. Enter the Chicago School of Data. We’ve done interviews, surveys, a convening, and are writing a book dedicated to how we shape Chicagoland’s data ecosystem to fit the needs of people in Chicagoland. Thanks to our documenters, the convening had an unprecedented amount of raw, in-the-moment documentation. We’ve classified these resources, archived them, and analyzed parts of the data already — data about how organizations in Chicagoland put data to work (how meta!). Now we need to make sure our work doesn’t collect dust. A taxonomy for Chicagoland’s regional ecosystem would turn our documentation into actionable intelligence.

I’m helping develop the structure of this taxonomy so it works for the community. The taxonomy is a way to format data about organizations who participate in the regional ecosystem. With structured metadata, we’ll be able to manage the knowledge we have about these organizations, such as organizations’ sizes, missions, and skill gaps. Regardless if this or a version of this specific structure is used, an established taxonomy for managing knowledge about data ecosystems is a good idea. It will accelerate the hardest parts of building capacity, building technology skills, and building coalitions. Designed to get data to work for people, a simple reference directory for organizations in the ecosystem would help organizations find worn paths to cross technology skill gaps. It would help organizations quickly match themselves with other organizations facing similar challenges, sharing similar successes. A taxonomy acts as a backbone for these kind of reference directories.

Originally, we classified Chicago School of Data participants by industry. Participants were either a university, government department, non-profit, or private company. These buckets were useful when we were finding people to interview. We wanted to get as broad a cross-section of the landscape as possible. We didn’t want to miss the perspective of any of our partners. Over time, though, we found that these buckets weren’t specific enough for our purposes. They weren’t organized in a way that told us anything about how our partners really used data. Ideally, we wanted look at an organization’s place in the ecosystem, its niche, and know exactly what support it needed around data and how else the organization could benefit — and be benefited by — the ecosystem.

Landscape Scan

I listened to and transcribed all the interviews and analyzed the pre-convening survey material. I tried to capture what were, by my lights, the main themes brought up during our scan of the ecosystem. I wrote a draft taxonomy in JSON. It’s okay if you don’t know JSON from a day salon. The drafts were guided by the idea that our data should work for people in the ecosystem, people we know and work with every day, and that it’d be easier to work with our project material if it were indexed. I classified ecosystem members, often non-profit organizations, as creators, consumers, and enablers of data. Wide nets, to be sure, so I introduced a few sub-classifications. The teased out data ecosystem looked like this:

- The data ecosystem has

- Creators

- Who open their data for free

- Who open their data for a price

- Who don’t open their data

- Because of technical capacity

- Because of cost

- Because of legal agreements

- Because of the public interest

- Because of other reasons

- Consumers

- Who only consume free data

- Who pay for some of their data

- Who use data

- To evaluate their own operations

- To evaluate other organizations’ operations

- And turn it into a digital product

- And turn it into a printed product

- Enablers who provide services and goods in the ecosystem such as

- Volunteers

- Consultants

- Funded organizations

- Paid organizations

- Creators

This taxonomy gives you a better sense of the ecosystem’s niches, but it amounts to a bunch of redundant lists of participants. An institution as big as Chicago Public Schools, say, is clearly a creator, consumer, and enabler of data in the ecosystem. CPS shares some data while protecting other data. Different departments use data in different ways. One department might focus on general national trends in education policy while another focuses on budget allocation versus tenure within one district. CPS is a good test case. Its multi-faceted role shows that members of the data ecosystem aren’t easily classified.

Survey Responses

After the convening, on September 19th and 20th, 2014, it was clear that the taxonomy needed revision. More detail was important, especially about how participants used data. Through a survey we found lots of ways data works in the ecosystem. I incorporated categories from our survey into the ecosystem, which changed the structure from:

- The data ecosystem has

- Consumers

- Who use data

- To evaluate their own operations

- To evaluate other organizations’ operations

- And turned it into a digital product

- And turned it into a printed product

- Who use data

- Consumers

to look like this:

- The data ecosystem has

- Consumers

- Who use data for

- Resource allocation

- Measuring impact

- Advocacy and outreach

- Understanding the needs of people served

- Donor development

- Operations

- Research

- Who use data for

- Consumers

Much better! This structure is more specific and it gives you a clearer picture about the many different ways data gets used by organizations in the ecosystem. This set of categories are specific to our ecosystem, given they were after all created in conversation with a specific group of partners mostly from the Chicagoland region for a conference. That said, my bet is that many organizations would say they use data for at least 1 of these 7 reasons. It’s important for any taxonomy to be flexible enough for people to enter and update survey data, though. Surveys are one of the most important instruments in civic technology.

Most of our survey categories are not mutually exclusive. When you look at our 246 participating organizations’ responses, the network of responses they share is extremely dense, with many millions of combinations. Without more metadata, we may as well reference the raw results of the survey, to learn, for example, that desktop spreadsheets are the most used tool among survey respondents. These survey categories are not enough when there’s already data available to see the ins-and-outs of the ecosystem.

Moar Metadata

People have worked hard to classify organizations. We can build off their work. Our taxonomy can incorporate IRS codes, property tax identifiers, budget, size, whatever’s useful. There are several classification systems for economic entities, such as S&P’s Global Industry Classification Standard, Forbes’s Industry Classification Benchmark, the UN’s International Standard Industrial Classifications. The 501(c)3 classification for a non-profit is one of twenty-nine other types of 501(c) organizations. Usefulness for these codes is measured by how many people actually use them to collect and organize data.

Categories developed by the National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCCS) are extremely useful for our ecosystem project and for other regional initiatives trying to get working inventories of their local data ecosystems. The NCCS categories are organized in their National Tax-Exempt Entities taxonomy.

Incorporating our survey data, NCCS categories, and a few federal codes, an organization’s place in the taxonomy might look like this:

- Organization name

- Type

- NTEE Code

- A54

- IRS Code

- 501(c)4

- EIN

- 43-219431A

- NTEE Code

- Size

- Revenue

- $1,000,000

- Employees

- 15

- Revenue

- Scan

- Uses data for

- Resource allocation

- Yes

- Measuring impact

- Yes

- Advocacy and outreach

- Yes

- Understand the needs of people served

- Yes

- Donor development

- Yes

- Operations

- Yes

- Research

- Yes

- Resource allocation

- Needs support in

- Outreach

- Yes

- Analysis

- No

- Outreach

- Survey question…

- Survey category #1

- Value

- Survey category #2

- Value

- Survey category #1

- Uses data for

- Type

An abstract version of this taxonomy is available in JSON here. The biggest design change reflects a guiding principle that our work should benefit people. During the first phase of outreach we cast the widest net, grouping organizations in buckets like “non-profit”, “university”, or “government”. These categories were useful when we were scanning the landscape and trying to include as many voices as possible. We changed the categories before the Chicago School of Data convening in September 2014 so that we could group organizations relative to how they worked with data. The JSON taxonomy classified organizations by whether they created, consumed, or enabled the data ecosystem. We added subfields and, after the convening, revised these subfields to include categories from our survey.

This version of the taxonomy does not use the “creator”, “consumer”, or “enabler” categories. It replaces these with organization names, which are now the ‘top’ categories in the structure. Under organization names I included a “Type” category with a few subfields, a “Scan” category to house our survey results, and a blanket “Size” category for other relevant fields, such as budget, employee numbers, and so on. It can be filled out with a simple Google Sheets template, and the template, in turn, could streamline the early research and design phases of capacity building.

Real working standards are hard to create. They’re products of collaborative work. Please add to or modify the taxonomy on Github.

Look out for the Chicago School of Data book, dropping January 2016.