This is the full report from Stephen Rynkiewicz on a National Day of Civic Hacking event, part of our Documentor Program.

The word heretofore hasn’t come up at a hackathon till now. But a roomful of developers are trying to define it, and thereby make the law simpler.

Lawyer Kingsley Martin sets them them straight. “Heretofore almost doesn’t have a meaning,” Martin says. “Many of these words you can just cross out and see if it changes the meaning, and in many cases it doesn’t.”

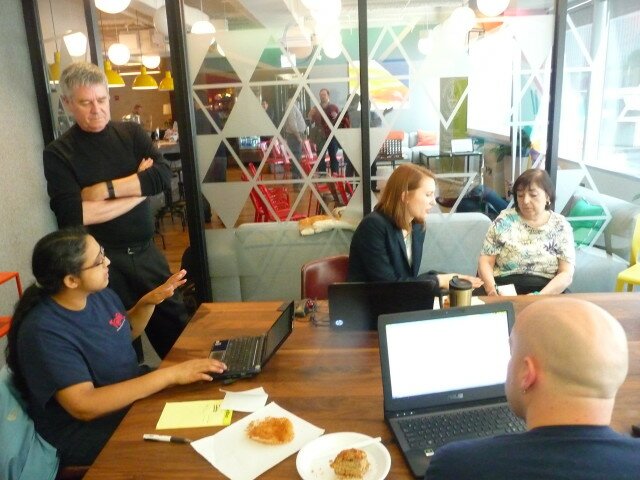

Developers gathered June 6 at Chicago’s WeWork, a shared office space. Early in the LexHacks event, they’re pressing Martin and other lawyers for resources that can help them win one or more of a half-dozen coding competitions.

Master of ceremonies Daniel W. Linna Jr., a Michigan State University law professor, thinks hackathons will attract advocates, project managers and data scientists as well as coders.

“I want lawyers to step up and embrace these technologies, so that we don’t have 80 percent of folks who have a need go without legal services,” explains Linna, an organizer of the Chicago Legal Innovation & Technology Meetup group. “We can do work with developers, designers, technologists, data analysts, lean thinkers to do that.”

Big law firms and tech startups already are automating trial discovery and other parts of the legal process. “Corporations were saying we can’t spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to manually review these mountains of electronically stored documents in litigation, or to conduct diligence in a large transaction,” he says. “That same technology has potential in so many other areas, predicting outcomes in cases.“

The hackathon starts with muffins, coffee and rules for the competition, where prizes range from $250 to $1,000. Hackers will organize as teams and produce their entries in less than 30 hours.

“The concepts and the ideas of everything we’re doing is open source,” says event planner Jon Pasky, a founder of the Techweek trade shows. “The sponsor will figure out what they want to do with the code.”

Event sponsors circulate among the hackers, acting as both resources and mentors. “Hopefully I can let people know what’s going on in the industry and some of the ideas we think about,” says Nischal Pathania, product manager for Avvo, an Uber-like app to request and rate lawyers.

Martin’s legal software firm KM Standards is putting up a $1,000 prize for the best plain English editing tool, an app that presumably could be grafted to its contracts website.

“My first job with a lawyer was in London,” Martin recalls. “I worked for a firm that prided themselves that they only worked for royalty and very wealthy families. We often had to go to the courts and bring documents that still had wax seals on them, written in almost Chaucerian English. This has just perpetuated itself.”

Laymen aren’t the only people who would benefit from a legalese translator. So would attorneys. “Lawyers believe that if they write in a highfalutin language, people will take them more seriously,” he says.

“In fact actually the contrary is true. The more skilled lawyer will write in a clear manner because they know what they’re doing.”

Lisa Colpoys, executive director of Illinois Legal Aid Online, organized one of two crowdfunded contests. “Our mission really is to break down the law, make it simple enough so people who can’t afford a lawyer can handle their legal problems,” Colpoys says.

“If you know anything about the legal system, and some of you may not, if you are indigent and have a criminal matter, the Constitution guarantees you a free lawyer,” Colpoys tells hackers. People about to be deported or evicted have no such assurance. “Then there’s a whole swath of the population that has legal problems and they can’t afford a lawyer. Because who can afford a lawyer these days?

“This system is scary. It’s complicated. If people want to go to court on their own, they typically don’t do very well, at least without education and some support,” Colpoys says. “Our challenge is to create some sort of a tool for people to evaluate whether it’s worth it to pursue some case or claim, or defend their case or claim.“

The lawyers and other mentors circulate among some 30 hackathon participants. Sisters Alyssa and Stephanie Romeo grab a booth and immediately start planning how to split time between another donor-funded challenge, a gamified legal checkup, and an app to flag confidential identification data. “We see each other a lot so we don’t have to talk about other things,” Alyssa says.

They decide on building a third app as well, a metadata parser. “Lots of people have contracts at scales they can’t really manage,” notes Michael Bommarito, whose firm LexPredict drafted the challenge. “When somebody executes or drafts an agreement, they throw it in a shared drive. It’s a Word document, it’s a PDF, it’s a Corel WordPerfect 7 document, who knows? How do you deal with all of that?”

Three veteran hackers, one on his 12th hackathon, take a conference room to start in on the crowdfunded contests, plus one more: an emotion detector for emails. “They’re really looking for a proof of concept,” says Anil Jason, who has competed in campus contests at Purdue and Wisconsin. “We can make one of them a little more polished.”

Next door, a trio from Michigan State’s law program picks the game, ID and emotion challenges. They confer with their offsite collaborators, two MSU grads at Apple and Slideshare.

“There are some real problems to be solved, but they’re not impenetrable,” he adds. “As a lawyer, I’m embarrassed that our profession does such a poor job of serving the public. I don’t think at all that it’s about more pro bono, or more legal aid. We’ve got this huge underserved marketplace, many of which are people who can afford to pay something. Why aren’t we trying to figure out a way to give them services, and do well by doing good?”

Pasky first organized legal hackathons to recruit developers to resolve a complaint he heard from tech startup founders. “They want to talk to their lawyer,” Pasky says, “but people I found in the small business and startup side don’t, because they’re afraid of the bills.”

With Ric Gruber, who worked his way through law school as a developer, Pasky launched Openlegal, the flat-fee website that recruits clients for their law office. “Every time we automate part of the process, we’re able to hire more lawyers instead of more admin staff,” Gruber says. “We’re saving our clients 30 to 50 percent because we’ve cut administrative waste.”

A day later, a raucous photography crew shares space with the hackers, their studio scattered with munchies. The developers, who’ve kept tidy workspaces late into the night, keep their heads down to submit their work.

“Three projects for two people!” Stephanie Romeo says. “We made it work, but it might be a little tough to repeat.”

“It was weird, like we all stayed in our groups and the moderators kind of hovered. We didn’t really interact with other teams,” said Dan Elliott of the MSU crew.

“Next time they should have like popup challenges where people can collaborate,” added teammate Irene Mo.

Documentation proved to be another challenge. ”We thought we would just submit the thing and send it off,” Mo said. “They actually have a questionnaire to explain our stuff, which we didn’t anticipate. After that, we wanted to be done 15 minutes beforehand so we could complete it on time.”

Martin and others have returned to judge in person, while Bommarito will watch hackers show their work online. “This is like an offshore team, where they do require a lot of instructional help, but only one team sought that,” Martin says. “In a class, some of the students that do best are the ones who say, I don’t know,” he says. “I’ll be curious to see how many created apps instead of concepts.”

A project plan might make a more persuasive entry than a finished app, Pathania suggests. “Some of these problems were impossible to solve in a day, especially when you’re overworked and sleep deprived,” he says.

“Unstructured documents are a pain,” say Ed Bryant and Chase Hertel, presenting their document parsing app.

Still, the teams have enough energy to present their apps, some more finished than others. After a judging conference call, the winners are announced:

- The Romeos’ emotion reader and Ed Bryant and Chase Hertel’s contract reader, both on GitHub;

- The Michigan State team’s Javascript ID redactor;

- A D3 website to estimate the chances of court success, presented by Amani Smathers;

- Two apps from the veteran hackers: a legalese translator and an Oregon Trail-style law game.

Team members and their submissions are detailed at ChallengePost.

Colpoys applauds the hackers for facing a big constraint in linking law and technology: a dearth of online records. “I’d love it if circuit courts would figure out a way to make their data accessible,” she says, “because it is all public record.”