Allison Arwady, chief medical officer at the Chicago Department of Public Health, discusses infectious disease rates March 29 at the Healthy Chicago 2.0 launch.

Chicago’s 2020 public-health plan is data driven. The city is putting numbers behind 60 health outcomes it wants to improve, from raising life expectancy to reducing infant mortality, gun violence, obesity and even binge drinking.

A 60-page report sets 82 public-health objectives to reach by the end of the decade. Many address larger issues that touch on health. Chicago aims to cut serious injuries in traffic accidents by one-third, and to boost walking, biking and public transit commutes 10 percent.

“The environment is right to bring in new data sets,” said epidemiologist Nik Prachand, the report’s co-author with deputy health commissioner Jaime Dircksen. Facing a 4 percent cut in the department’s funding, health professionals are trying to influence choices throughout the $7.8 billion city budget.

At the report’s March 29 unveiling, the South Shore Cultural Center displayed city maps from the report, with areas of the greatest need colored red. On measures of crime, housing and economic development, the most-afflicted areas matched the neighborhoods with poor health outcomes. (Smart Chicago Collaborative presents much of this data on its Chicago Health Atlas website.)

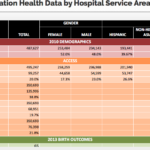

“Teen birth rates continue to fall,” said Dr. Julie Morita, the city’s health commissioner. Chicago has blown through a 2020 citywide target set in 2011. The city also met its 2011 goal for cutting smoking among high-schoolers, and is on track to cut HIV diagnoses.

“But disparities persist,” Morita said. “This is not acceptable.” The city counts more than 70 per 1,000 teen births in West Garfield Park and West Englewood, but less than 5 per 1,000 in other neighborhoods.

Communities that score low for educational, social and economic attainment also show the most births among teenagers, plus higher risks of outcomes from asthma to homicide. “It became clear to us that this should drive our work with Healthy Chicago 2.0,” Morita said – not only treating poor health but addressing its root causes.

Top priorities in the 2020 plan include behavioral health, adult and adolescent health, chronic and infectious disease, and violence. Each interest comes with numeric targets for change. The behavioral health plan would cut ambulance calls for suspected opiate overdoses 20 percent and mental-health hospitalizations 10 percent, and would step up treatment for severe psychological stress by 10 percent. Specific communities get special attention, including a pledge to cut suicide attempts by 10 percent among gay or transgender teens.

Local residents and health workers helped guide the broader approach in 18 months of agenda-setting meetings. Attendees at the plan’s launch say the approach makes sense: They see similar connections among bad results of all sorts.

“Typically at a restaurant we have found a correlation between labor violations and health and sanitation violations,” said Felipe Tendick Matesanz, development specialist at Restaurant Opportunities Centers United.

Tendick Matesanz was part of a team that set the plan’s community development strategies. It aims to improve well-being by boosting savings and assets among low-income residents. The city still needs baseline measurements for that goal.

The plan’s first deliverables are steps toward better metrics. The city will adopt research principles and launch a “public health data partnership” by July 1. Prachand wants to track health inequities using retail, insurance, land use and other metrics. He also wants to draft standards for data integrity and privacy.

“We’re looking to shake up the private sector,” he said. “People complain about government data being slow, but there’s a firewall around private data. It’s not available to you.”

To build a framework for evidence-based policy, the city pledges to launch a functional data network by July 2017. By the end of 2017, it should have infrastructure in place for training and for publicizing research.

Six public meetings in May will give an overview of the plan and ask for ideas.

Caregivers are enthusiastic about the expansive view of the city’s health. “It’s going to take the whole community of people to work cohesively together,” said public-health nurse Donna Feaster.

“For all of us this is part of our mission. In the end, it’s about people who need services,” said Karen Reitan, executive director of the Public Health Institute of Metropolitan Chicago, who served on the report’s steering committee. She believes the city’s goal-setting collaborators in the health community now will be motivated to act.

Reitan thinks the push for metrics will make agencies more responsive too. “There’s a school of thought, which I don’t agree with,” she said. “If it did not get recorded, it did not happen.”