Here’s some coverage of the Foodborne Chicago project today.

The main story was on the front page of the Chicago Tribune: Food-poisoning tweets get city follow-up: Health authorities seek out sickened Chicagoans, ask them to report restaurants. It was a very complete story, with detailed custom graphics on the process we follow to manage incoming tweets:

The same story was used as the front page of the Red Eye in a package called “#DirtyDining: Trending Toxic:

Here’s the full story:

Food-poisoning tweets get just desserts

Health authorities seek out sickened Chicagoans, ask them to report restaurants

By Monica Eng, Chicago Tribune reporter

August 13, 2013

When Juan Anguiano fired off a tweet about a bout of food poisoning in April, he thought he might hear back from sympathetic friends or pick up a new follower.

“I wasn’t expecting the city of Chicago to tweet me and ask me to file a report,” said Anguiano, an editor for Univision.

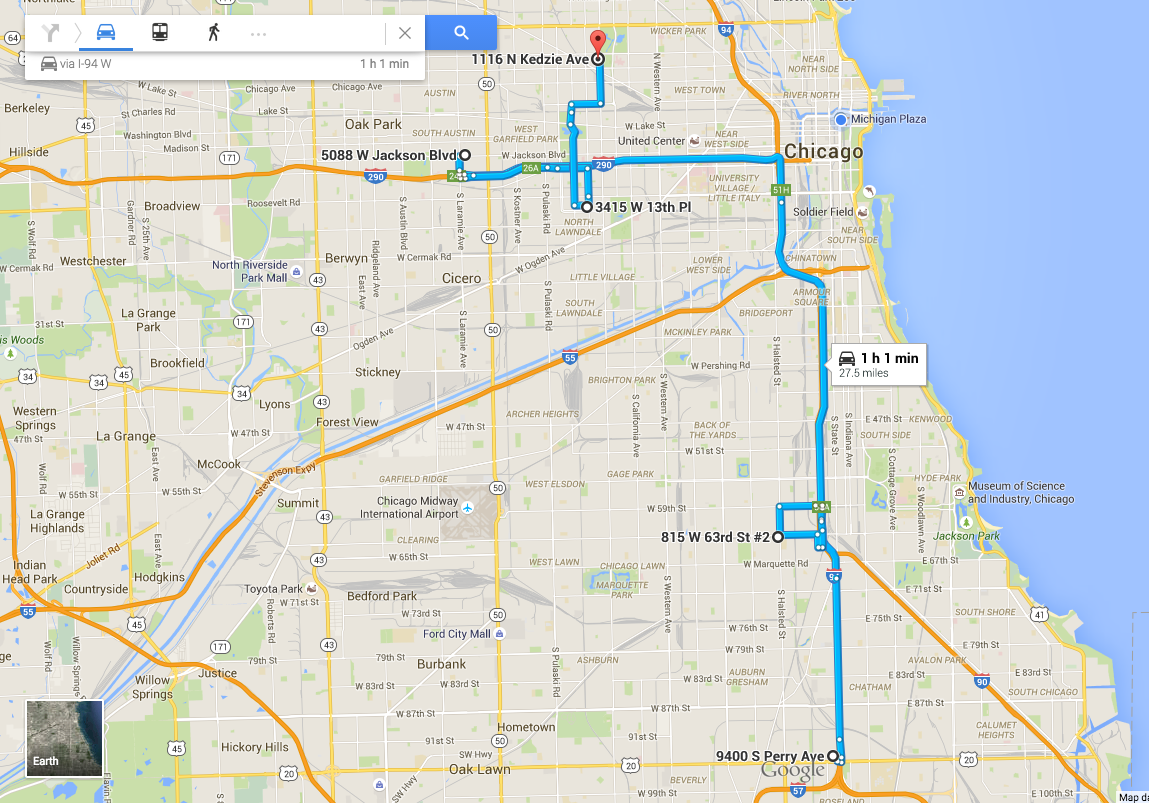

Still, that’s pretty much what happened. Since April, an automated application has been searching Twitter for posts that include the words “food poisoning” by people who identify themselves as Chicagoans.

Several volunteers then contact some of those people and suggest they complete a form that goes to the Chicago Department of Public Health. “I actually filled it out and thought it was awesome,” Anguiano said.

The health department says more than 150 Chicagoans have been contacted since the initiative, called Foodborne Chicago, began. In its first month, reports triggered 33 restaurant inspections, some of which uncovered violations, officials said.

“We wanted to try to reach out to Chicagoans in many different ways, and we know that a lot of people are on Twitter,” said Health Commissioner Bechara Choucair. “If they are experiencing food-related illness, they won’t always pick up the phone and call us, but they will tweet it.”

But is combing Twitter for the words “food poisoning” really a useful way to crack down on dirty food service establishments? Although many people who become sick blame the last thing they ate, experts say that meal is often not the culprit.

According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, foodborne pathogens can trigger symptoms of illness a few minutes to several weeks after contaminated food is ingested, which makes it tricky to pinpoint the source of food poisoning.

Food safety attorney Bill Marler is well aware of the vastly different incubation periods for foodborne pathogens, but he thinks the idea still may end up being helpful — or, at least, not hurtful.

“If the health department is using it for people to say, ‘Hi, I suspect I just got sick from this restaurant’ or ‘I just went to this place and it’s just a mess,’ then I don’t see a problem with doing inspections based on that,” Marler said. “They should be doing inspections anyway. So it’s probably no more or less accurate to use inspections to respond to a consumer complaint, even if the consumer might be incorrect. They are either going to find a problem or not find it.”

Marler said he could see how restaurants might object, but the Illinois Restaurant Association said it had no complaints.

“There is nothing more important than food safety in our restaurants,” association President Sam Toia said in a statement.

Foodborne Chicago, which tweets as @foodbornechi, was developed by Smart Chicago Collaborative, which describes itself as “a civic organization devoted to improving lives in Chicago through technology” and counts the city of Chicago as a founding partner.

The app is billed as part of an ongoing effort by the health department to use technology to make its services more transparent and accessible to citizens. In the past couple of years, officials have placed all health department inspections online, nearly in real time, and posted progress on various health initiatives on a regular basis.

With the expansion of social media, complaints of suspected food poisoning, news of regional outbreaks and general whines about food service establishments have gained audiences well beyond their previous scope.

Marler noted that after a listeria outbreak in Canada a few years ago, researchers examined the number of people from the region who had searched online for the bacteria’s name. “Big data” may be useful “in tracking outbreaks when you can see that a lot of people are searching for the same help,” he said.

Some Chicago tweeters who heard from Foodborne Chicago said they thought twice about reporting their favorite restaurant but hoped doing so would protect other people and help identify larger outbreaks.

“Food poisoning can be kind of vague, so whether or not they use social media, it is going to be difficult to find claims that have provable grounds,” said Nicole Rohr, an interactive content producer at WYCC-Ch. 20 who got sick in May. “But it’s worth looking into, especially if there is an establishment where multiple people get sick. That’s when I think it can be really helpful.”

Marler agreed that explicit tweets with locations and symptoms could help connect the dots.

“I could see where I’m in the hospital and I ate at these three restaurants and then someone tweets that they ate at one of them and now they have bloody diarrhea, too,” he said. “You could see where that could generate the outlines of an outbreak. But it’s got to be used very wisely.”

Triathlete Myles Alexander, who tweeted about food poisoning that he suspected contracting at a favorite Italian restaurant, said he thought the new program might best be used to detect repeat offenders.

“If they get enough red flags about one specific restaurant, that can show that they need to pop on by and do another inspection,” said Alexander, who fell ill after eating fish soup.

Some of the tweets about food poisoning that are accessible through Foodborne Chicago’s Twitter feed call out restaurants by name. According to Marler, even if the information turns out to be inaccurate, a libel claim against the tweeter is unlikely to succeed.

“It’s complicated, but the short answer is that it has to be knowingly false,” Marler said. “The only time a customer would have a problem would be if they absolutely knew that the food was not the cause of their illness but they said it just to harm the restaurant.”

Commissioner Choucair said most of the people contacted through the program are “excited to know that we are listening.” He sees it as another way for government, citizens and technology to join forces to make Chicago a better place.

“We are always looking for new opportunities to leverage innovations to improve food safety,” he said, “but we need the help from Chicagoans.”

Even if that help is just sharing — or even over-sharing — about your tummy troubles on Twitter.

Copyright © 2013 Chicago Tribune Company, LLC