In February, our team attended the Knight Media Learning Seminar (MLS) in Miami. We spent time with a dynamic mix of philanthropists and journalists discussing civic technology and the battle against misinformation.

Regardless of whether content is accurate, it is still disseminated across a flawed information infrastructure defined by inequitable access and echo chambers. As I participated in MLS, I was reminded of this reality and how it interacts with our digital inclusion work at Smart Chicago and the Chicago Community Trust.

Leading journalists, technologists & city grant makers will gather in #miami for Media Learning Seminar https://t.co/YTkvTLq3Kc #infoneeds

— Knight Foundation (@knightfdn) February 12, 2017

How can foundations meet #infoneeds? New @knightfdn lab seeks answers, invests in @ChiTrust: https://t.co/ntm8gYuY5H

— Microsoft Chicago (@MSFTChicago) February 16, 2017

Our information infrastructure has been shaped by concentrated poverty and the lasting impact of segregation in our cities. Just recently, the National Digital Inclusion Alliance published a report pointing to systemic discrimination and “broadband redlining” in Cleveland. This has brought us to 2017 where, despite the fact that we feel saturated with news and notifications, the human the built systems that create and deliver our civic news are still not built to serve or even reach all Americans.

Access & adoption remains a problem, even in 2017

A talk on the future of media by Amy Webb highlighted some of the most interesting trends in technology today: artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and robotics. After the talk an audience member stood up and asked, “How does access/adoption of the Internet impact this conversation on the future of tech engagement?”

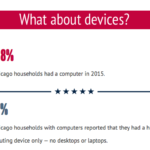

About 1 in 5 American households do not have Internet in the home and the same is true for the City of Chicago. Unfortunately, unconnected households are also more likely to be minority, older, and report lower educational attainment. So, at conference like this where the latest and greatest trends are in the forefront of everyone’s mind, it usually becomes someone’s job to ask: “is the rising tide lifting all boats?”

When talking about meeting the #infoneeds of segregated communities, we should discuss #digitalinclusion https://t.co/yMJsxBEHHk @freepress

— Denise Linn (@DKLinn) February 13, 2017

It’s not just about access to the Internet, either. It’s also about access to computers, STEM education, digital learning opportunities, and content creation opportunities. While we work to understand the commercial potential and ethical implications of new technology, we can’t forget that some residents lack the speeds, devices, and connectivity that a majority of us take for granted. Without that basic access point to information in the Digital Age, will the divides between the haves and the have-nots only widen? This is why work like Connect Chicago, training at the Public Library, and institutions like YWCA, LISC Chicago, Chicago Citywide Literacy Coalition, and Blue1647 are vital to our city.

There is a rising literacy bar in an age of misinformation

At Knight MLS several fake new cases were discussed. Each story reinforced how the Digital Age has risen the bar for news literacy. A clear demonstration of this came again in Amy Webb’s talk when she highlighted her recent piece in Mother Jones:

Facebook and Twitter algorithms prioritize posts with high “engagement”—popular ones—and links that their customization code predicts you will click on. All over the web, your past digital behavior results in targeted ads, some of which resemble news stories. Content recommendation companies like Outbrain and Taboola place sponsored links on publishers’ websites for a fee but are only marginally effective in policing fake news and propaganda. On the contrary: All these companies make money off clicks, and they’ve got mountains of data proving we’ll choose provocative headlines over serious ones.

“You’re worried about fake news now? You haven’t even thought about what’s next” @amywebb on VR + fake news #infoneeds

— George Abbott (@garthurabbott) February 14, 2017

“Moscow thanks you for sharing its cute cat pics” https://t.co/z18DeH28wQ … via @MotherJones @amywebb re: UN for the Internet #infoneeds

— Denise Linn (@DKLinn) February 14, 2017

Increasing News Literacy in an Age of Fake News: https://t.co/8NeVlqtiOi #ChicagoTonight @McCormick_Fdn @jennychoinews pic.twitter.com/6f4Y6KCMZI

— WTTW (Chicago PBS) (@wttw) February 15, 2017

Being an informed, discerning reader also requires us to understand where our stories come from and how technology presents stories to us in the first place. Given these needs, how should we rethink the relationships between basic literacy, digital literacy, and technology literacy? Studies have shown that today’s youth, often assumed to be tech literate based on age alone, have trouble telling when news is fake.

Mozilla’s Web Literacy Framework speaks to this new literacy complexity — wisely pushing beyond basic literacy or basic computer literacy to being a thoughtful consumer of web content. In particular the “Read” portion of the framework requires not only that learners absorb the words on a screen, but also learn how to search, navigate, synthesize, and evaluate content.

Mozilla’s Web Literacy Framework speaks to this new literacy complexity — wisely pushing beyond basic literacy or basic computer literacy to being a thoughtful consumer of web content. In particular the “Read” portion of the framework requires not only that learners absorb the words on a screen, but also learn how to search, navigate, synthesize, and evaluate content.

Philanthropy has a role to play in addressing this new literacy standard. The Prototype Fund, supported by the Knight Foundation, the Democracy Fund, and the Rita Allen Foundation (deadline April 3, 2017), is a timely example of how philanthropy can help test new ways to fight misinformation. The fund seeks to catalyze new collaborations between media and technologists:

We’re open to diverse perspectives on topics ranging from, but not limited to, the role of algorithms in news consumption, methods for separating facts from fiction, building bridges across ideological divides, and strategies for ensuring journalism organizations are authentic to the communities they serve.

Wynwood Walls of Miami, FL | February 2017

This was my second year attending Knight MLS. Just as it did last year, this conference challenged me to think beyond our field of civic technology and consider its role within the broader media movement. What I think makes this convening so exciting is the specific combination of stakeholders and view points that are brought together. Conversations are solutions-focused and there are many lessons to be learned from other cities. More importantly, when philanthropists, journalists, technologists, and other community champions discuss our information needs together, we increase the odds that the resulting ideas will be valuable and sustainable.