Today I will take part in the Digital Inclusion Meets Civic Tech panel at the 2015 Code for America Summit. It’s great to talk about such a timely issue with Deb Socia of Next Century Cities, Demond Drummer of CoderSpace, Chike Aguh of EveryoneOn, and Susan Mernit of Hack the Hood.

Since important conversations like this never seem long enough, I wanted to share my thoughts here.

I’m the new Program Analyst at Smart Chicago managing the Connect Chicago initiative and other projects like the Chicago School of Data. I care about open data, Internet access, faster networks, and improving digital skills. A question I’m particularly interested in is this:

I’ve noticed that a lot of common answers involve versions or combinations of the following:

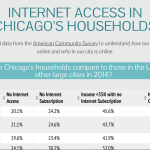

Do we think these answers are enough? When the White House released its analysis of the digital divide in the U.S., they defined being on the right side of the digital divide as having Internet access in your home. While increasing at-home subscriptions is certainly a desirable trend, is it enough to declare victory in a city?

I would say no — not in 2015. Since Internet access has become more essential and its place in our hierarchy of needs has shifted, we should expect that percentage to increase naturally, even without policy interventions. We should acknowledge that, in 2015, Internet access in your home does not necessarily give you equal opportunity in the digital economy. Things like speed, type of online activity and skill are just as key to unlocking the potential of a connection.

Also an increase in citywide broadband adoption doesn’t speak to geographic and demographic gaps in Internet access; rather, the disadvantaged or historically underconnected people and neighborhoods that see that increase are the marginal successes we care about.

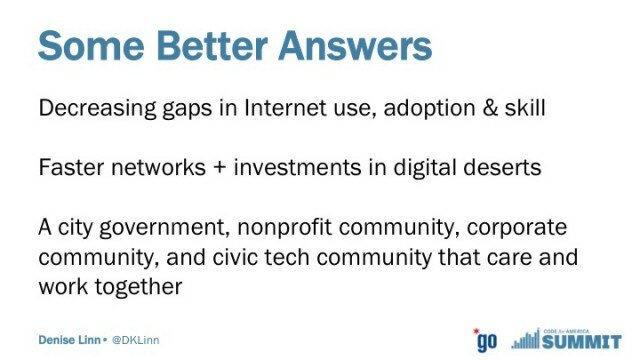

We need to go further:

Getting more people online in a city, getting a faster network, or having a robust nonprofit sector does not necessarily mean that city is digital inclusive. We should care about gaps in skill and use in addition to gaps in adoption. We should acknowledge that connections themselves are not the end game— rather, educational attainment, technology sector growth for all, workforce development and increasing civic engagement are the true outcomes. As program managers and policymakers, we should plan our evaluations around these truths.

Also, faster networks alone are not enough to make a city digital equitable. It’s what you do with the network that matters. Last year as a graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School, I wrote, “A Data-Driven Digital Inclusion Strategy for Gigabit Cities.” You can see a summary one-pager here or read a blog post about it here. One thing I observed was that some high poverty urban census tracts had very high connectivity. Why? Because they tended to be dense, walkable, and house several community anchor institutions – schools, churches computer labs or community centers. While digital inclusion programing is often built on top of these trusted neighborhood institutions, cities should care about digital deserts – areas with low connectivity and low access to digital assistance.

Another question of interest:

Here are the “almost” answers – a vision of the civic technology movement that is admirable, but arguably incomplete:

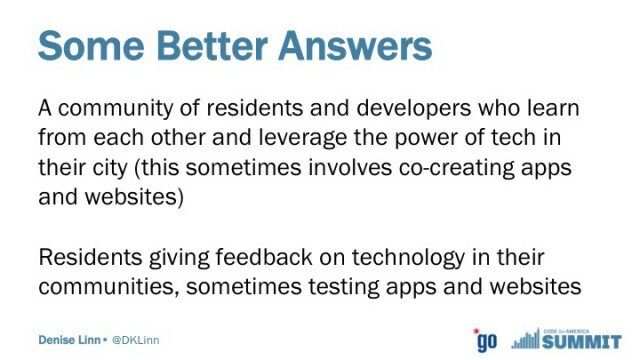

The answers below go one step further. Much of this sentiment is captured in the great work of Laurenellen McCann in Experimental Modes of Civic Engagement in Civic Tech and Sonja Marziano in the Civic User Testing Group (CUTgroup).

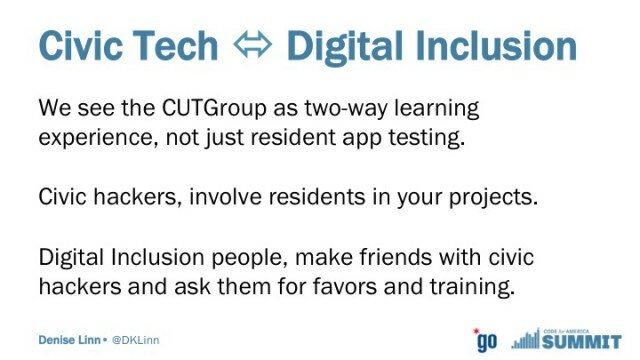

The benefits of civic technology do not travel in one direction. Civic hackers have as much to gain from including diverse, non-expert and non-technical residents in their work as the residents themselves do. Residents seek ways to learn about solving social problems with technology, data or mobile applications. Civic hackers seek to create tools that solve relevant problems and truly work for everyone.

Despite the way we talk about them, civic tech and digital inclusion are not separate movements with separate missions. Both seek to make residents’ lives better through technology. The differences lie in the method and associations. When a resident thinks of a civic hacker, they might think of a person who seems smarter than them coding away at a hackathon. When a resident thinks of a digital trainer, they might think of the volunteer in the library public computing center. Wouldn’t it make both jobs easier (and the city better) if the civic hacker could also talk to the library trainees and the digital trainer attended the hackathon? Let’s make that happen.

Digital inclusion professionals have a lot to offer the civic tech community. These trainers and program professionals are experts in community outreach, skilled in training, and are the boots on the ground in their neighborhoods.

Unfortunately, digital inclusion professionals are not always paid to or encouraged to think about civic tech. I feel lucky in this respect because I work for Smart Chicago – an organization built for Chicago specifically to care about both civic tech and digital equity. The only thing I have to do to form a digital inclusion-civic tech partnership is Slack Sonja Marziano or wheel my desk chair three feet behind me to her work station!

These are her people:

These are my people:

This is just one place where civic tech meets digital inclusion in Chicago.

We’re thinking of ways Connect Chicago (a network of aligned programs, public computing centers and trainers across the city) and the CUTgroup can work together to make Chicago the most connected, skilled, digitally dynamic city in America.

One idea? Let’s get feedback from CUTgroup’s 1000+ testers on the digital skill offerings in the city. How easy is it for them to learn what they want? What resources are lacking? What resources exist that they don’t know about? We want to collect all the unknown unknowns. Chicago can better understand the “user experience” of its residents, not in relation to a new application or website, but in relation to the digital access and skills ecosystem in their city and community. As it turns out, a significant chunk of our CUTgroup testers rely on mobile and public Wi-Fi:

29% of 1,000+ people in @CUTGroup cite “public wifi” or “phone with data plan” as primary connection to the internet. pic.twitter.com/kWgDnYvfyL

— Smart Chicago (@SmartChicago) September 25, 2015

Are there other creative ways digital inclusion projects and the civic tech community can partner and strengthen one another? We’re confident. Let’s have that conversation. If you have ideas, we want to hear about them.

Talking to each other is fun, but doing stuff is better. Here are actionable items we can take home after the Summit:

Civic hackers, pledge to involve five people you don’t currently know in your next project. Embrace civic user testing groups as opportunities to learn, teach and inspire; measure success not only the number of apps created and tested, but in the number of people engaged. Digital trainers and digital inclusion program managers, go to a hackathon or civic tech convening, present a specific wish list, and take your trainees and co-workers with you.

To follow the panel on Twitter, see our hashtags #CfADigInc and #CfASummit and follow me at @DKLinn.

Here’s the presentation as a download: