Health workers treating obesity in children are looking beyond what they see in clinics, to what’s at play in Chicago parks.

“Can you imagine camping in Chicago within 15 minutes of downtown?” said Zhanna Yemakov, Chicago Park District conservation manager. At the quarterly meeting of the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children, Yemakov outlined park plans for the roughly 1,000 acres of Southeast Side brownfields now among park holdings.

Other speakers addressed the city’s playgrounds, plazas and pocket parks. “Our focus is what we call a socio-ecological approach, where we look at all the factors that influence childhood obesity at all levels,” said Adam Becker, CLOCC executive director, after the June 9 conference. The focus extends beyond individual cases to family, community and the broader social and political environment.

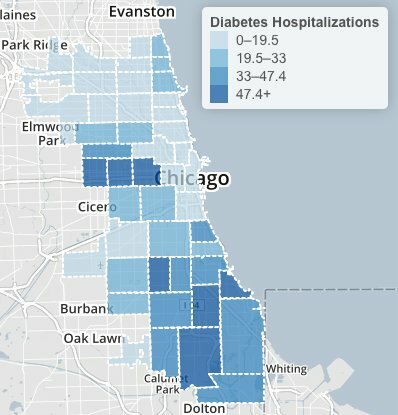

Chicago Health Atlas: Diabetes hospitalization per 10,000 residents, 2011

A 2013 city study finds Chicago Public Schools students have above-average obesity rates – 48.6 percent of sixth-graders were overweight or obese. In 8 of the city’s 77 community areas, fewer than one-third of students fell outside the healthy range; in 15 communities, it was about half.

Overweight and obesity do carry long-term risks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In children and adolescents, they include cardiovascular disease and elevated blood sugar levels that can lead to diabetes within a decade.

Obese children also are more likely to become obese adults, with higher rates of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, cancers and osteoarthritis. The Chicago Health Atlas charts variations by neighborhood in several such adult conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, and breast and colorectal cancers.

“If you’re focusing on one you’re not going to solve the problem,” Becker said. “We try to measure impact as best as we can, but with obesity it’s just so complicated. You can’t just say A equals B. The lines are very indirect.”

The city will develop the Calumet Open Space Reserve as what Yermakov calls “a place where it feels wild, but at the same time has elements that make it seem comfortable and safe. “ Planners tried to balance concerns in community meetings, from preserving bird’s nests to controlling snakes and squirrels.

About 40 acres of the 300-acre Big March site at 114th and Stony Island will be developed starting next year as a $5.5 million bicycle park large enough for national contests. Yermakov says the district must address community concerns that the obstacle course would cater to “white rich folks,” she says.

In 300 neighborhood parks, a $44 million project replaces playground equipment over five years. “We took this initiative on to crate more challenging playgrounds that were more physically responsible and more adaptable to the communities that we were in,” said senior project manager Michael Lange.

Tradeoffs were made to finish 246 playgrounds since 2013, including a cheaper surface for the 78 planned this year. The Mindmixer and EveryBlock websites were engaged to generate neighborhood interest, along with volunteer work days.

Physical activity has been incorporated into community-managed gardens, said Robin Cline, assistant director with the NeighborSpace land trust. Jardincito at 23rd and Whipple was landscaped this spring with rocks logs for jumping and grassy berms for tumbling tots.

“It’s kind of odd that we would have to create spaces like that, but that’s where we are,” Cline said. “There is information that has come out recently that many, many kids do not how to roll down hills.”

Pedestrians now are considered in building street features like State Street’s Gateway median. “I don’t think anybody ever thought of it as any sort of space for pedestrians,” said Janet Attarian, who runs the Chicago Department of Transportation’s Complete Streets program.

New performance spaces at Woodard Plaza, near the Kimball-Milwaukee-Diversey intersection in Logan Square, are part of a city People Plaza program to remake traffic plazas. Attarian says she’s working with community groups to learn “how we can give people the tools, which some of the time is about actually getting government out of the way.”

Members of the CLOCC obesity network attempt to measure fitness in their own programs, not all for clinical reasons. Playground supervisors in the Urban Initiatives program send paper surveys home with field-trip notices.

“I throw what I call data entry parties, where I buy the entire office lunch and we enter data all day,” said Lauren Johnson, the nonprofit group’s development manager. “We’re just collecting data ourselves for the purpose of bettering our programs.”

Johnson told fellow program evaluators in a working group that coaches keep data on children’s activity, including body-mass measurements.

“We have scales all over the office – people are constantly going out to schools with a scale – and I buy little tape measures,” she said. Data are being migrated to a tailored Salesforce customer database.

Of the city’s measurable public health goals for children, only one addresses obesity: lowering the rate of high-schoolers eating less than five servings a day of fruits and vegetables. For five years the rate has held near the 2020 target, 77.8 percent.

The obesity consortium developed shorthand for encouraging fitness in children, now used nationwide. The 5-4-3-2-1 Go! campaign calls for daily consumption of 5 fruit and veggies, 4 glasses of water, 3 servings of lowfat dairy, 2 hours or less of screen time and an hour or more of physical activity.