This is the fourth piece in a five-part series exploring how to develop civic technology with, not for communities. Each entry in this series reviews a different strategy (“mode”) of civic engagement in civic tech along with common tactics for implementation that have been effectively utilized in the field by a variety of practitioners. The modes were identified based on research I conducted with Smart Chicago as part of the Knight Community Information Challenge. You can read more about the criteria used and review all of the 5 modes identified here.

MODE: Lead from Shared Spaces

Communities are built around commons— collaboratively owned and maintained spaces that people use for sharing, learning, and hanging out. Commons are the foundation upon which all community infrastructure (social, technical, etc) is built and are often leveraged by multiple overlapping and independent communities.

Although often thought of as semi-permanent physical spaces, like parks or town centers, commons can also be digital (i.e. online forums, email lists, and wikis), temporary (like pop-ups or weekend flea markets), or a variety of other set-ups beyond and in-between.

A commons is a resource, offering tools, news, and know-how that both community insiders and outsiders can wield. Tapping into a commons not only helps identify social and technical infrastructure, it provides a key opportunity to listen and learn about what matters most to a community. The following two tactics look at how civic tech practitioners can not only use commons for collaborative work, but can contribute to their stewardship, as well.

Leverage Existing Knowledge Bases

Knowledge commons are spaces where people collect and access information, be it archival info (like one would get from a library) or news (like one gets from a neighborhood listserv).

Depending on the circumstances and the folks behind the wheel, the creation of a knowledge commons can itself be a form of civic technology— a tool for a community to use for its own benefit.

Depending on the circumstances and the folks behind the wheel, the creation of a knowledge commons can itself be a form of civic technology— a tool for a community to use for its own benefit.

DavisWiki is a hub for both hyperlocal history and current events in Davis, California. Launched in 2004, DavisWiki started as an experiment in collaboratively surfacing and capturing unique local knowledge that was otherwise locked in the heads of neighbors or lost in search engines. The site gained popularity by coordinating with existing social infrastructure, such as the university system in Davis and the local business community, and within a few years residents had contributed over 17,000 pages.

As more residents use DavisWiki, the platform’s role has changed. In addition to being a popular catalog, knowing that DavisWiki was available as a knowledge commons has enabled residents to leverage the platform for additional civic ends over time. For example, the wiki was part of coordination of the public response (and record-breaking rally) to a police officer pepper-spraying a student on the UC Davis campus in 2011 and has been used to explore, discuss, and collaborate with government a number of local planning initiatives.

Public Lab is a different sort of knowledge-based community: although many of the folks who participate in Public Lab (via their wiki, email listservs, in-person meetings, and other forums) work in their own local contexts, the community associated with Public Lab is international in scope, bringing together citizen scientists from around the globe who are researching and crafting inexpensive DIY tools for environmental science that anyone can use.

In this way, Public Lab plays the role of a bridge, connecting many knowledge commons together in one great public-facing resource that can boost local work by giving it a broader audience and more data inputs.

Leverage Common Physical Spaces

Although the network model of Public Lab enables a high degree of exposure for local work, nothing says “free PR” quite like door-knocking or standing on your neighbor’s roof to install an Internet router. Both the Detroit and Red Hook Digital Stewards instances lead with this idea, leveraging common spaces in their communities (neighborhoods and city districts) to plug into existing social infrastructure and get community members on board and involved.

Approaching technology development with an eye towards the physical world also enables an additional dimension of sustainability. While both Digital Stewards instances are ultimately about developing digital commons, by tapping into physical resources and the social structures that maintain them, the Stewards extend the communal care and maintenance to include the new technology over time.

Up next: Mode #5: Distribute Power.

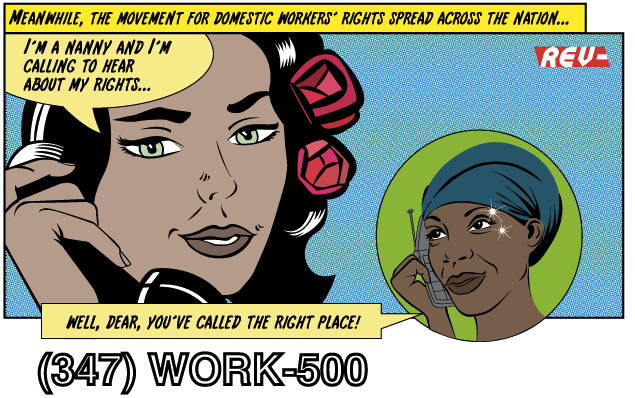

Similarly, The NannyVan’s Domestic Worker Alliance App was also the product of a longer-tail two-way educational initiative. The app, a phone hotline structured around a fictional, educational show, was developed

Similarly, The NannyVan’s Domestic Worker Alliance App was also the product of a longer-tail two-way educational initiative. The app, a phone hotline structured around a fictional, educational show, was developed

Using this criteria, I analyzed dozens of “civic technology” projects, mostly, but not exclusively within the US. I disregarded whether or not the projects or creators identified with “civic tech,” looking instead at whether or not the “tech” in question was created to serve public good. (Our interest, after all, is to explore the “civic” in “civic tech.”)

Using this criteria, I analyzed dozens of “civic technology” projects, mostly, but not exclusively within the US. I disregarded whether or not the projects or creators identified with “civic tech,” looking instead at whether or not the “tech” in question was created to serve public good. (Our interest, after all, is to explore the “civic” in “civic tech.”)