Earlier this month, we gathered 30 community technology practitioners from around the country together for a convening about the Experimental Modes of Civic Engagement in Civic Tech. Over the course of a day, we dug into big questions about civic tech conceptually (and whether and how and when it actually fits the work that we do), how to document our work for ourselves and others, and the strategies we use to do what we do.

You can see full documentation of our meeting and conversation here.

At the end of the day, we took time to reflect on our discussion. Below, I’ve rounded up excerpts from the group’s final thoughts and organized them by theme.

Major Takeaways

Language

The words that we use to describe our work. “Civic tech” is a new term that, while literally descriptive of the work of the practitioners we brought together, doesn’t always resonate with these practitioners or the communities they work with. (See more here.) We talked in detail about how the interest in this new idea was destructive…as well as how it could provide opportunity.

Greta Byrum: “Think about words like “disruption”: it captures the interest in short term impact, but it has this problem of not speaking to the long term of real social change and transformation, and it changes our understanding of what work does.

Civic tech is the hot new thing. Can we use it in a way that’s useful? Can we use it to fuel the work we do? Or will this term undermine the work that we do?”

SHAPING THE NARRATIVE AND THE PRACTICE

Storytelling. Much of our afternoon was focused on questions about documentation: where and how we collect our work and share our models.

Dan O’Neil: “We’re in a sliver of a sliver in the tech space. We need to move from glorifying the anecdotes, the stories we tell to get funding, to sharing the modes and methods and the ways that we do that. That’s how revolutions happen, when people share their understandings, when people come together and share with each other the exact ways that we do things.”

Adam Horowitz: “Where are the stories about the innovations I’ve heard about today told and how they can be told bigger? We read about Uber in the paper, not about community tech. What’s the role of storytellers in making this work more noticeable?”

Maegan Ortiz:“I’m thinking about how this tech space was created: who was in the mind of the folks who created it and who wasn’t, and how, by using community organizing models, we can either replicate that or we can use it and imagine it and push it to be something different that may even disrupt, interrupt the original vision.”

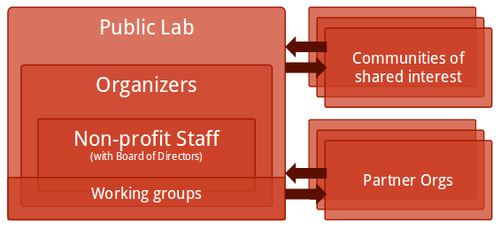

Community Organizing

More than their use and creation of community technologies, what united the people in the room was their focus on community organizing. What is a collaborative process to make tech if not the collective, organized effort of a group of people looking to make their lives better?

Demond Drummer: “I’m a tech organizer. I’ve always had a problem with the distinction between organizing and tech. But from this conversation today, particularly with Maegan (Ortiz), I’ve come to own and better understand the deliberate, conscious, purposeful use of the “tech organizer” as a tool and a field of play where power itself is contested.”

Diana Nucera: “It’s clear from this gathering of community organizers that we’re in a time where community organizing extremely important in government. So the question is, how do we get government to adopt community organizing? It’s always been clear that government should adopt community organizing, but it’s now clear there’s a need for it. The use of technology has revealed that need. As we go forward from here, I hope we stay true to community organizing practices.”

Earlier in the day, we talked “ingredients for engagement”: what qualities an organizer instills to not only get people in the door, when it comes time to work together, but to keep them there, make them feel comfortable, and enable an environment where people as individuals and together as a collective can share power and take action. The practices and ideas that came up over and over included “invitation”, “permission”, “comfort”, and “active listening”.

On comfort:

Sabrina Raaf: “I keep thinking about how Chicago has this interesting history in the art world of walk-ups and basement galleries traditionally called ‘uncomfortable spaces’. I’m struck by the conversations we had today about ‘comfort,’ and hoping hoping for new tradition of ‘comfortable spaces’.”

On tension:

Allan Gomez: “It’s important to remember the default settings. The status quo. The default ends up being such an inertia-creating force, it’s difficult to change. So I want to semantically challenge the idea of “comfort” because tension needs to be created to change the default. If we’re looking for real innovation, we need to look for examples grounded in people’s lives from all over the world. Language of reclamation. And we need to reflect on how we want to use this tech versus how this tech forces us to behave.”

Bringing the focus into the immediate presence, Tiana Epps-Johnson reflect that even our work in the room that day was an impression of the comfort/tension dynamic:

Tiana Epps-Johnson: “Comfort in spaces has a lot to do with the people in the room. It’s refreshing that a conversation about civic tech is not dominated by white men, and it’s not a coincidence that the people who think about community reflect that.”

Expanding on this idea, we discussed that much of our conversation from the day would have been the same if we called it a “community organizers” convening instead of a “community tech” convening, but the people who chose to come (and opt out) would have changed.

Marisa Jahn: “One of the things that struck me about the different people in the room today is that everyone identifies as a something and something else. Multiple identities. I also have a varied background between advocacy and tech and arts stuff. It’s always seemed ad hoc: I used to do things because they interested me or because I wanted to learn or to help people.

Now I’m thinking about how the way people arrive at tech is through relationships, through connections that validating all the ampersands, all the hats that people wear, all the paths taken.”

Many of the Experimental Modes are focused on relationships. Relationships are community fuel and sinew. They are the foundation upon which all community collaboration — tech related or not — is built. Without understanding how social ties work and without investing energy in creating strong, genuine social ties, truly collaborative projects are impossible.

Whitney May, exploring this idea in her own work with local election officials, came up with a formula based on the “ingredients for engagement” discussion earlier in the day:

Information + Invitation = Participation.

Whitney May: “Local government really struggles with reaching out to people, with invitation. And so do we. Our project focuses so much on information, but we need to do more inviting.

Technology as its best is a way that expands_____. Insert what you will here. For tech to expand community organizing and access to civic information, for me, if I distill that down, it’s actually just participation. So how can we use tech to expand participation?”

We do more inviting.

Jenn Brandel: “Information + Invitation = Participation. Thinking about this at a metal level, before I was invited into this conversation about civic tech, I didn’t realized I belonged here — or in community organizing. Now I feel like I’m part of something far bigger than I realized.”