Collaboration is at the heart of the Smart Chicago Collaborative and is essential to achieving the goals of the civic technology movement. The hard problems that need to be solved can not be solved in isolation.

Collaboration is at the heart of the Smart Chicago Collaborative and is essential to achieving the goals of the civic technology movement. The hard problems that need to be solved can not be solved in isolation.

There is an art to collaboration. Being in a collaboration means that you’ve agreed that your partner or partnering organization is already highly capable at what they do. It means that you’ve agreed upon a common goal and a plan of action to achieve that goal. Being in a collaboration means that you’ve opened up the lines of communication for the duration of the project.

Working collaboratively isn’t always easy – particularly when the project involves multiple partners or complex problems. Things can get exponentially more complex each time you add a moving part. Here’s some thoughts on how I’ve approached collaborative project management in my consulting practice and in my work at Smart Chicago.

Building a plan

One of the most difficult things about project management the natural tension between sticking to a plan and the need to be able to adjust the plan if something doesn’t go according to plan. This is important because things never go perfectly according to plan. The planning process is important for working on collaborative projects because you’re going to have multiple parties running activities that are independent of each other in order to accomplish the goals of the project. If there’s not a well defined plan, the project could steer off course. Here’s our workflow for planning projects.

Step One: Gut Checks – Define the goal, ensure the activity matches the goal, and ensure the goal is in line with your organization’s mission statement

The first part of taking on a project is establishing the goal and ensuring it the activity being proposed will get the results you want. You’re essentially asking the question, “At the end of the day, what do we want to be the result from this project?”

This is a different than saying, “We want to run a hackathon.” If the goal is to have an app that gets resident feedback, then you don’t need a hackathon. There are already existing products that do that. If the intended results are, “We want to engage the civic tech community around environmental data we just released”, then a hackathon would accomplish this. It’s perfectly OK to have one idea about how to get something done and then change tactics once you review it. Once you determine that the goal will achieve the objective you can move on.

The other thing that you will need to check for is that the project goals are in line with your organization’s mission. Would getting these results also help your organization achieve its mission? Is your organization’s mission to help with FOIA requests? Does taking the time to write, print, and distribute a newsletter help you achieve this? Is your organization in the business of creating technology tools to help store data? Does running a event help with this? If the answer to the question is no, then it may be advisable to say no to a project. It isn’t always easy to say no, but performing this ‘gut check’ before you begin is a good way to ensure the resources of your organization are being spent wisely.

Once you perform these ‘gut checks’ and everything checks out, you’ll be ready to begin constructing the plan.

Step Two: Work backwards from the goal and make a list of everything you’ll need

Think about the activity that you’re setting out to do. For example, you want to host a hackathon helping an environmental agency engage with the developer community about new environmental data. What does that look like?

At the end of the event, you’d have people presenting on prototype projects to all event participants after a day exploring the data sets. (Needs: Venue, microphones, projectors)

You would then work backwards through the day and mark down items that come up. For example, before the presentations the hackathon would have teams working with the data and coming up with prototypes. (Needs: Wifi, power strips, things to write down brainstorming notes on, lunch, breakfast.) They’d also need an orientation into the data and the problem set. (Speakers for the morning, links to different data sets)

You would continue to work backwards until you get to your current point in time. For our hackathon example, this means going over getting people to come to the event. (Needs: RSVP page, blog posts, invites, social media outreach).

Working backwards helps ensure that you don’t forget anything in the planning process. At the end of the exercise, you’d have a list of items that you would need to have ready as well as a draft of a possible timeline.

Step Three: Take inventory of resources and identify gaps

The next thing you want to do is to ensure you have the right resources to achieve the goal of the project. This often means taking stock of the resources all the organizations have at their disposal and matching them with the needs of the project. This is often the very reason to work on projects collaboratively. It allows two organizations with different strengths and resources to combine them into achieving a goal. There might be times when you check the list of needs and resources and discover that you’re lacking in an area. At that point, you have the option of hiring a vendor or reaching out to an organization with resources you’re looking for and partnering up.

For our hackathon example, I have lots of experience running hackathons. However, Smart Chicago doesn’t have any subject matter expertise working on environmental issues. This would be a gap to fill.

As you work through matching needs with available resources, you’ll also notice a list of items that nobody can really provide – but can be easily purchased or ordered through a vendor. (For our hackathon example, this is food and flip charts.) This help with our next step.

Step Four: Determining a budget and harmonizing the plan with the budget

Once you determine the project needs and what resources you have on hand, it becomes easier to establish a budget. Depending on your project, you can price out some things pretty easily. (For our hackathon example, it’s a simple process to start calling up different catering companies and getting estimates for food.)

If your project involves hiring a developer, designer, consultant or other freelance position, then additional steps may be involved. You may need to put out a Request for Proposals (RFP) that include the deliverables you need and how soon you need it. We’ll get into the details of writing good RFPs in a later chapter. For right now, understand that it may take some time for vendors to put together responses to an RFP depending on what you’re requesting.

A final thing you should account for when making a budget is taking into account the cost of your own time. Even if you’re volunteering, you should account for the hours you spend working on the project.

As the costs of the project begin to shape up, you’ll get a sense of if your organization has the resources to pull off the project or if the organization needs to obtain outside funding through grants or sponsorship. Alternatively, your organization may have been awarded a grant to fund a project – and you have to ensure that your project plans fits into the budget.

Step Five: Writing out Scope of Works and Memo of Understanding (MOU)

At this point, you should have a pretty good idea of what you want to do, what it’s going to cost, who is doing what, and a general timeframe. Now it’s time to get those thoughts down on paper. The most common ways to do this for collaborative projects are Scopes of Works and Memos of Understanding (MOUs).

Scope of Work

A Scope of Work is a document that’s written in the planning stages of a project. They’re often written in the context of one person or organization hiring another. If there’s more than one partner that’ll be doing the work, there’ll be more than one scope of work. Scopes of Work lay out what work is to be done, how quickly it’s to be done, what report backs need to be done in connection with the work and (in the case of a vendor/client relationship) what the estimated compensation will be. Good scopes of work are flexible enough to allow the person or group doing the work to best decide how it gets done, but strict enough to say what the result will be. (Good example, I need a website that helps people find public computing locations. Bad Example: I want a website written in Python that let’s people find public computing locations by searching a Google Fusion table.)

Scopes of work can either be written by the client or the vendor as a response to an request from a client. It doesn’t matter so much who starts the process, but rather that both parties agree on the final scope of work. Even if both parties have a pretty good understanding of what needs to be done, going through the process helps to make sure everything is crystal clear. It also helps set limits on the work to be done in case the project turns out to be much more complex than first realized.

Once the scope of work is finalized, they can often be turned into contracts that organizations can use to pay vendors or consultants.

Memo of Understanding

A Memo of Understanding (MOU) is similar to a scope of work on that it sets up what work is to be done, who is doing it, the expected timeframe, and what report backs are needed. The main difference between a Scope of Work and a Memo of Understanding is that a MOU Is used between two parties when no money is being exchanged.

The MOU is important because it sets up exactly who is doing what at the very beginning. If there’s ever a disagreement on who is supposed to be doing what, both parties can refer to the MOU.

MOUs and Scopes of Work are essential to collaboration because they establish a clear understanding of the project. Once these are signed and agreed upon – or turned into contracts if needed – you can then start on the project.

Step Six: Iterative Process: Checking in on progress and making adjustments

One of the drawbacks to technology projects is that they take a lot of time and effort to create. Given the costs of hiring developers, technology projects can also get expensive very quickly if projects are not managed correctly. Additionally, if project managers wait until something has been delivered it and it comes out wrong, it can take a significant amount of time to correct.

An iterative process favors a short cycles of work, check-in, and adjustments. During the check-ins, the expectation is not to have made progress in leaps and bounds – but rather to have made smaller updates. Because the progress is in small increments, it’s much easier to make adjustments than it after a team has spent several weeks working on a product.

It also means that you can catch blockers early so that they can be resolved quickly. Does the team need more resources? An extra team member to get it done? Is one of the vendors not up to the task and need replacing?

There will be some cases when the blocker is large enough that the time and effort it would take to resolve it outweighs the cost of doing something else entirely. For example, your team is working on an app to analyze a dataset that was received from a Freedom of Information Act Request. It turns out that the data is far more dirty than first anticipated with missing data, misspelled entries, and obvious typographical errors. The amount of time that would be needed to clean it up far exceeds the timeline first established. The question that you would face as a project manager is do you continue the course and accept a longer timeline? Do you narrow the scope of the project and drop the data that is the most difficult to clean up? Or do you add additional resources to help with cleaning up the data? There’s no specific right answer, but these are the kinds of challenges that may pop up as managing collaborative projects. (For reference, when Smart Chicago was faced with a similar problem we narrowed the scope.)

In addition to discovering blockers early on, working iteratively also allows for testing of products in front of real users. When the team has something that’s somewhat close to the final product, they can have the project undergo user testing to ensure it’s going to work for the user like it’s supposed to. If it doesn’t, then rather being a failed project, the team runs through another iterative cycle and makes improvements before launching.

Check-ins with partners

You should also schedule regular check-ins with partner organizations. This lets everyone know where everyone is at, what the current blockers are, and if there’s any adjustments that need to be made to the plan. By keeping everyone well informed, it also helps work more collaboratively. Surprises are great for birthday parties, but not when managing collaborative projects.

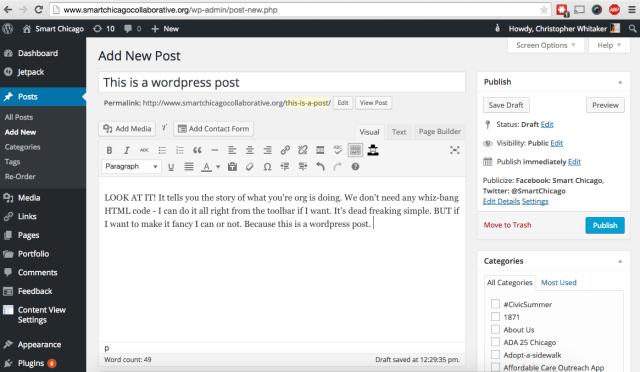

Step Seven: Once it’s done

Once you’ve completed the activity that you had planned out before, it’s time to let people know about what you did. Whether it’s a new app launch, successful hackathon event, or a new guide on how to run civic technology projects – you should tell people about what you did. You can do this through blog posts, social media, or email campaigns.

It’s important to tell people about the project so that people can learn from your actions. The more people learn about your actions, the more it advances the field.

The US City SDK was created by the US Census Bureau to be a user-friendly “toolbox” for civic technologists to connect local and national public data The creation of the CitySDK came out of the desire to make it easier to use the Census API for common tasks that their developer community asked for. For the past two years, the Census Bureau has been engaging with the developer community to see how they use the API. After seeing the most commonly used functions being built out of the API, the Census Bureau has now built those functions into the SDK to make it easier for developers.

The US City SDK was created by the US Census Bureau to be a user-friendly “toolbox” for civic technologists to connect local and national public data The creation of the CitySDK came out of the desire to make it easier to use the Census API for common tasks that their developer community asked for. For the past two years, the Census Bureau has been engaging with the developer community to see how they use the API. After seeing the most commonly used functions being built out of the API, the Census Bureau has now built those functions into the SDK to make it easier for developers. One of the problems that we sometimes encounter in the technology space is that we say things like, “Oh, just use this piece of software that I assume you know about.”

One of the problems that we sometimes encounter in the technology space is that we say things like, “Oh, just use this piece of software that I assume you know about.”

Google Drive is a set of office tools where the documents live on the internet rather than your hard drive. It includes Google Docs (Word), Sheets (Excel), Slides (Powerpoint), and a few other applications. Having documents that live online means that you can access them from anywhere including your phone.

Google Drive is a set of office tools where the documents live on the internet rather than your hard drive. It includes Google Docs (Word), Sheets (Excel), Slides (Powerpoint), and a few other applications. Having documents that live online means that you can access them from anywhere including your phone. Slack is an internal chatroom. It’s a more modern version of IRC with many more additional features including being able to integrate with everything from Google Drive to social media channels. Slack allows you to add different channels in addition to the standard “General” and “Random.” When we use Slack, we have a separate channel for all of our projects. Slack also has a powerful search feature that can be useful when trying to remember something that the group was talking about from weeks ago. If your organization ends up sending a lot of small two sentence emails, this may help cut down on that.

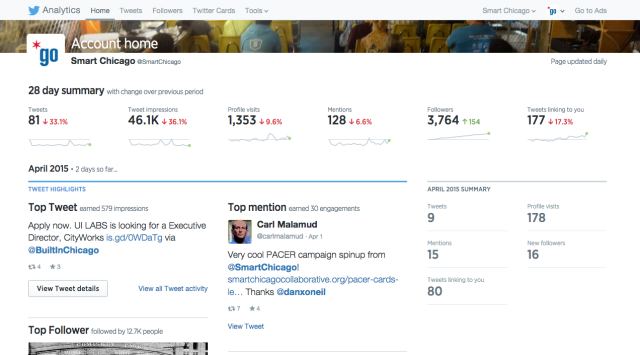

Slack is an internal chatroom. It’s a more modern version of IRC with many more additional features including being able to integrate with everything from Google Drive to social media channels. Slack allows you to add different channels in addition to the standard “General” and “Random.” When we use Slack, we have a separate channel for all of our projects. Slack also has a powerful search feature that can be useful when trying to remember something that the group was talking about from weeks ago. If your organization ends up sending a lot of small two sentence emails, this may help cut down on that. Email is still one of the biggest ways that organizations communicate with their communities. Mailchimp helps organizations by first helping to craft well designed eye-catching emails, but also by helping organizations manage email campaigns. You can pick customized lists of recipients, monitor opens/reads, and even conduct A/B testing of different email campaigns.

Email is still one of the biggest ways that organizations communicate with their communities. Mailchimp helps organizations by first helping to craft well designed eye-catching emails, but also by helping organizations manage email campaigns. You can pick customized lists of recipients, monitor opens/reads, and even conduct A/B testing of different email campaigns.

One of the quirks of both working in technology and the civic sectors is that both sectors tend to use a lot of jargon and abbreviations that makes perfect sense in context, but can baffle outsiders.

One of the quirks of both working in technology and the civic sectors is that both sectors tend to use a lot of jargon and abbreviations that makes perfect sense in context, but can baffle outsiders. At

At