At Smart Chicago, we’re developing methods for resident engagement with the Internet of Things. This year, I will be leading a series of activities and events that will bridge the current gap between the urban sensors measuring our city and the people who live in the city. We believe that ‘smart city’ technology should benefit and be informed by the public and that we should work towards a smart city that truly works for everyone.

Fortunately, there is a framework in place to build on from the UK. On April 28, 2016, Professor Pete Edwards and Caitlin Cottrill from the University of Aberdeen presented at the University of Chicago Convening on Urban Data Science. Their project in Aberdeen is called “Trusted Things & Communities: Understanding & Enabling A Trusted IoT Ecosystem.” The goal of the project is to create a community-based approach to building trust into the Internet of Things (think: networked sensors gathering data).

At the 2016 Convening on Urban Data Science at the University of Chicago, Dr. Cottrill from the University of Aberdeen discussed privacy and the Internet of Things

Presenters from Aberdeen emphasized the importance of authentic engagement to a trusted ‘smart city.’ The text from the slide above is an excerpt from “The Internet of Things: Making the Most of the Second Digital Revolution” by the UK Government Office for Science and created context for the conversation:

“There are more connected objects than people on the planet. The networks and data that flow from them will support an extraordinary range of applications and economic opportunities. However, as with any new technology, there is the potential for significant challenges, too. In the case of the Internet of Things, breaches of security and privacy have the greatest potential for causing them.”

The “Trusted Things” Project in Aberdeen

The “Trusted Things” project in Aberdeen aims to inform and engage residents on the public value, governance, and privacy implications of a local Internet of Things project. It focused primarily on the Tillydrone district of Aberdeen.

The “Trusted Things” project in Aberdeen aims to inform and engage residents on the public value, governance, and privacy implications of a local Internet of Things project. It focused primarily on the Tillydrone district of Aberdeen.

Here is a summary of the questions of interest and main goals of the “Trust Things” project from the original grant description:

What are the appropriate governance arrangements covering IoT deployments? How do we deliver meaningful accountability? How can we develop an understanding of the interplay between individuals and devices, and the wider relationship to social/cultural norms? What are the attitudes of citizens and communities to privacy and risk in an IoT context? How should risks and benefits be communicated? How do users make informed decisions to judge the trustworthiness of information?

Answers to these (and the many other questions that will certainly emerge) will lead us to develop prototype solutions that will be evaluated with members of the Tillydrone community. Our ambition is to create a means by which a user can review the characteristics of an IoT device in terms of its impact on their personal data, answering questions such as: What type of data is it capturing? For what purpose? Who sees it? What are the (potential) benefits and risks? They also should be able to exert a degree of control over their data, and be guided to assess its reliability and accuracy.

To find out what residents want from urban sensors, ask them

Professor Pete Edwards remarked how, when asked “Do you Trust the Internet of Things?”, the natural response of residents was, “What is the Internet of Things?”. The “Trusted Things” approach, therefore, checked assumptions about residents’ knowledge, opinions, and priorities by simply engaging with them — talking to real people about a complex, but important piece of urban technology.

From the experience of the “Trusted Things” project, here is an inventory of all of the information and control requested by the public from their local sensors:

People want to know who is using data and for what end. They want to know who controls the devices and who controls the data. People want access to the data and potentially to interact with the resulting data. They feel they have the right to change the devices and data’s behavior. Residents also believe that the they deserve notice of changes in the sensors’ capabilities or data gathering processes.

An example of a resident connection with the Internet of Things? In Aberdeen, there are sensor-enabled bus stops that citizens can interact with on their mobile devices. The mobile app tells interested residents what the sensor is doing, what it’s measuring, and what that bus system data will become.

Privacy & the Internet of Things

Professor Caitlin Cottrill overviewed the privacy concerns and governance issues surrounding sensor devices in the Internet of Things.

Professor Caitlin Cottrill overviewed the privacy concerns and governance issues surrounding sensor devices in the Internet of Things.

Cotrill pointed out that the Internet of Things is inherently different than other forms of data collection residents might be familiar with. Why? Sensor data isn’t static like census data. Instead, it’s spatially and temporarily detailed. Becauses these devices collect data continuously and always in the same specific place, these data have the potential to point to more sophisticated information: habits, routines, and health indicators, for instance. If the sensors happen to be capable of collecting personally identifiable data, privacy is a potential public cost.

This threat is why “privacy by design” is embraced. “Privacy by design” simply means that personal privacy is considered throughout the development of an Internet of Things project. Privacy is an ongoing concern that shapes the planning, building, engagement, and deployment or an urban sensor. Privacy isn’t an afterthought.

Cotrill also explained that it was a best practice for the creators and collectors of data to write and share an official privacy policy. It is also customary to publish governance or administrative procedures that surround the collection and sharing of sensor data.

To read more about privacy principles surrounding smart city technologies, see “Privacy by Design: 7 Foundational Principles,” developed by Ann Cavoukian, the former Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, Canada.

Chicagoans & the Internet of Things

Last week, the Chicago Tribune wrote two stories about the Array of Things project — an urban sensing project operated out the the University of Chicago Urban Center for Computation & Data and Argonne National Laboratory. Both stories raised issues of privacy and resident engagement.

Last week, the Chicago Tribune wrote two stories about the Array of Things project — an urban sensing project operated out the the University of Chicago Urban Center for Computation & Data and Argonne National Laboratory. Both stories raised issues of privacy and resident engagement.

The first, “Array of Things sensor network to be installed in the Loop this summer” overviewed the new timeline for deploying the sensors in the Loop this year. It also referenced the Array of Things privacy policy to be released in mid-May — a policy collaboratively created by the City of Chicago, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Smart Chicago, and several other partners. The second article, “Chicago seeking ‘smart city’ tech solutions to improve city life,” echoed privacy concerns:

But already the city’s nascent efforts to collect environmental data are sparking concerns about further erosion of individual privacy in a city already outfitted with police cameras, red light cameras, in-store cameras and public transit cameras. And, perhaps most critically, some observers question whether the collection and analysis of data will lead to meaningful improvements to urban life, as advocates suggest, or just enrich big tech vendors.

These concerns make authentic, inclusive resident engagement and the lessons from Aberdeen all the more relevant for Chicago. If the University of Aberdeen case recommended one central idea, it was this: community-based and community-centered dialogue is a key ingredient to implementation.

To read background on the Array of Things urban sensing project go to this website. To read more about Smart Chicago’s civic engagement work in Array of Things, visit our project page.

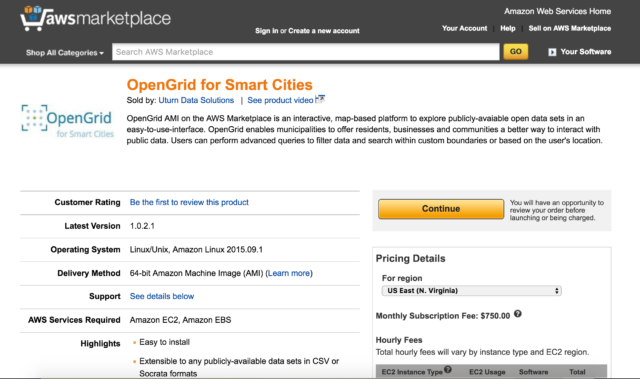

Today our partner, Uturn Data Solutions, launched Open Grid for Smart Cities, with support from Smart Chicago.

Today our partner, Uturn Data Solutions, launched Open Grid for Smart Cities, with support from Smart Chicago.

The “Trusted Things” project in Aberdeen aims to inform and engage residents on the public value, governance, and privacy implications of a local Internet of Things project. It focused primarily on the Tillydrone district of Aberdeen.

The “Trusted Things” project in Aberdeen aims to inform and engage residents on the public value, governance, and privacy implications of a local Internet of Things project. It focused primarily on the Tillydrone district of Aberdeen.

Professor Caitlin Cottrill overviewed the privacy concerns and governance issues surrounding sensor devices in the Internet of Things.

Professor Caitlin Cottrill overviewed the privacy concerns and governance issues surrounding sensor devices in the Internet of Things. Last week, the

Last week, the